Interlocking Spheres: The Rise of Cotton

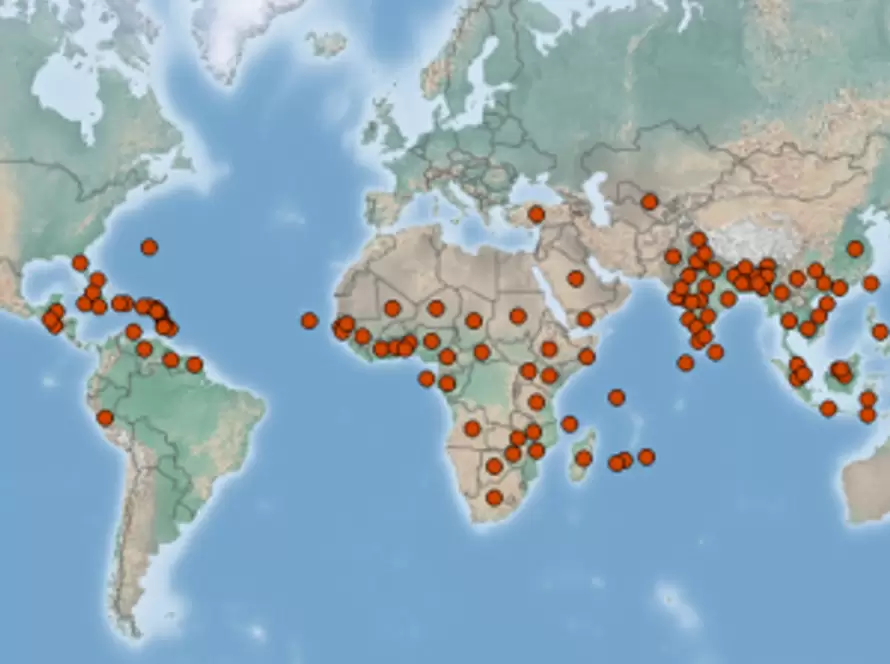

Before the 14th century, no single fiber dominated textile production across the globe. Wool thrived in Europe, while cotton gained prominence in Asia, forming two distinct textile spheres. Europe, particularly England, relied heavily on wool as a cornerstone of its economy, while India mastered cotton production by 1400, becoming a global specialist. Limited raw material supplies and regional ecosystems reinforced these separate spheres, with cotton and silk reaching Europe as luxury items, enriching upper-class wardrobes but remaining scarce.

Indian Cotton and Global Disruption

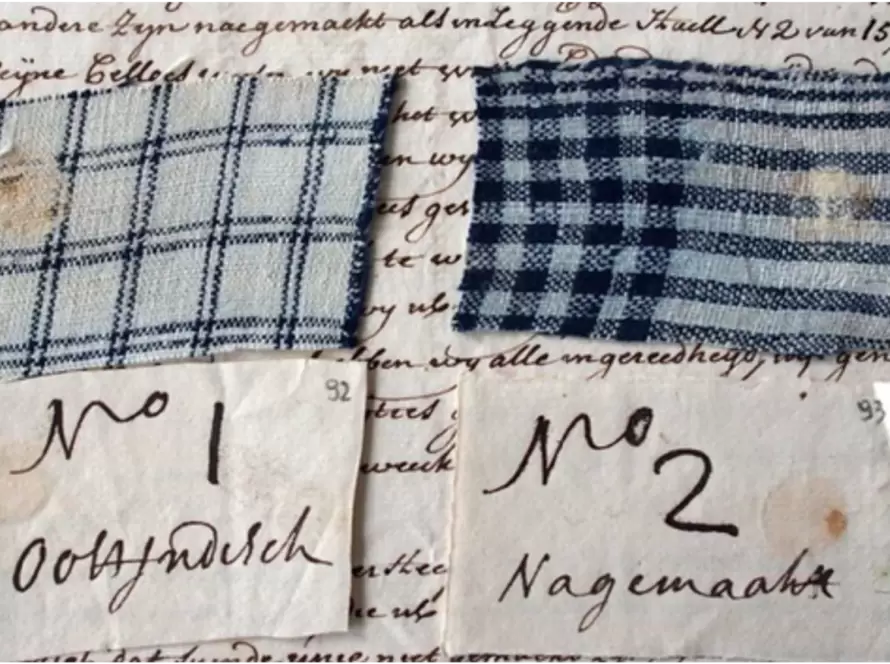

Indian cotton textiles, lightweight, vibrant, and easy to maintain, gained immense popularity in Southeast Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and eventually Europe. These textiles challenged local industries, threatening wool and silk but complementing linen. In Europe, cotton transformed notions of hygiene and aesthetics, first as an exotic luxury and later as a rational and modern commodity. By the 17th century, rising demand led to import restrictions and the establishment of local printing industries, yet European production lagged behind India’s finesse in spinning and hand painting.

Industrial Transformation and India’s Decline

The Industrial Revolution, marked by innovations like Arkwright’s water frame (1765) and the flying shuttle (1733), allowed Europe to reinvent cotton production. By integrating Indian techniques with European engineering, new textiles like copper-printed fabrics emerged, reshaping consumer preferences. However, imperial policies devastated India’s spinning industry, and by the 1860s, Europe’s flourishing cotton industry had overtaken global markets. The interlocking spheres of wool and cotton gave way to a new textile order, driven by Europe’s industrial ingenuity and consumer demand.